AI Can Make a Sandwich

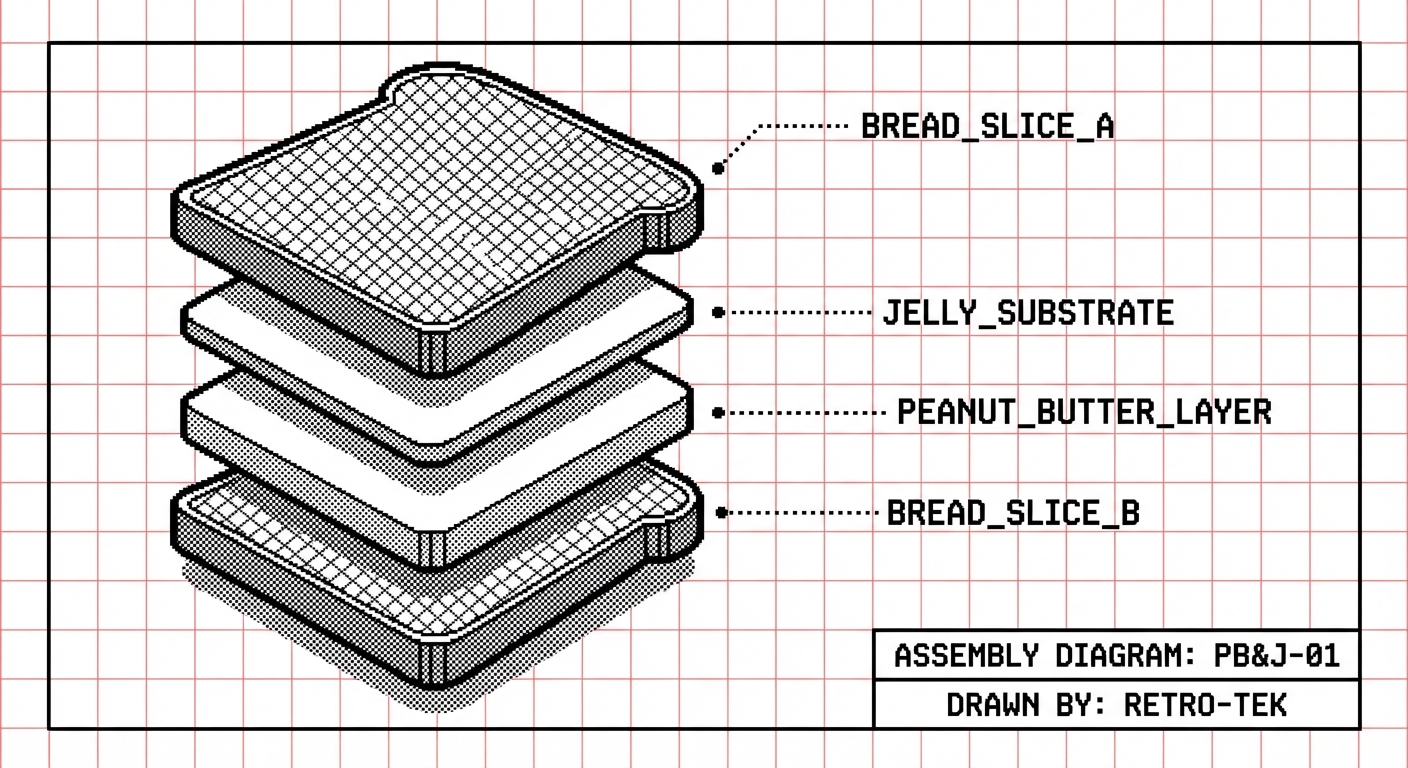

There's a famous exercise in introductory programming courses. You ask a student to write instructions for making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. They write something like:

- Get bread

- Put peanut butter on bread

- Put jelly on bread

- Put the pieces together

Then you, the instructor, act as a "dumb computer" and follow the instructions literally. You grab the entire loaf. You smear peanut butter on the crust. Chaos ensues. The lesson: computers are stupid. They do exactly what you tell them. Nothing more, nothing less. As engineers, our job was to think through every edge case, every micro-step, every possible interpretation.

Chris Pine's Learn to Program captures this beautifully. The computer doesn't know what a sandwich is. It doesn't know that bread comes in slices, that jars have lids, that knives exist. You must teach it everything, explicitly, painstakingly.

For decades, this was the foundational mental model of software engineering: you are the brain, the computer is the muscle.

That model is now breaking.

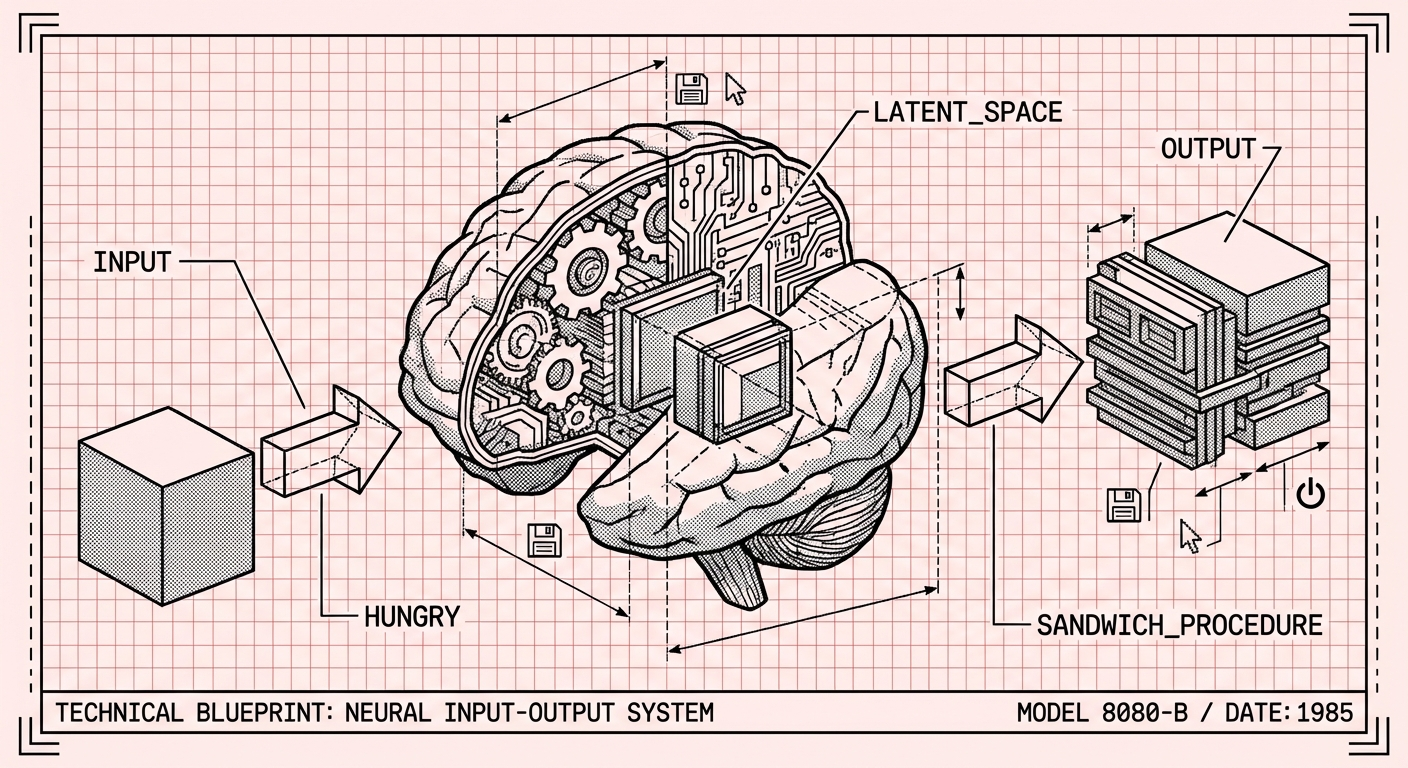

The Latent Space Shift

LLMs don't work like traditional programs. They're not executing instructions step-by-step. They're navigating something called latent space — a high-dimensional representation of everything they've learned during training.

Think of latent space as compressed knowledge. When you trained on billions of documents — cookbooks, tutorials, Stack Overflow threads, Reddit arguments about the correct ratio of peanut butter to jelly — you don't store it all verbatim. You encode relationships, patterns, concepts. The knowledge is latent: present but not explicit.

When you prompt an LLM to make a sandwich, it doesn't need you to explain what bread is. It knows bread. It knows slices. It knows the cultural context of a PB&J. It knows that "make a sandwich" implies a sequence of actions that a human would recognize as sandwich-making.

The LLM can make a sandwich.

Not because someone wrote a makeSandwich() function with explicit steps. Because the concept of sandwich-making exists in its latent space, ready to be activated by the right prompt.

The Overcorrection Problem

Here's where it gets uncomfortable for engineers.

Our entire training — years, sometimes decades — has been about being explicit. Precise. Unambiguous. We've been rewarded for thinking through every step, every edge case, every failure mode. We write documentation. We write tests. We specify contracts.

The instinct to over-specify can actively harm your results with LLMs. When you write a prompt that's too prescriptive you constrain the model's ability to leverage its latent knowledge. You force it into a narrow channel when it could be drawing from a vast reservoir.

It's like giving a master chef a recipe for toast. Sure, they'll follow it. But you've just wasted everything they know about bread, heat, timing, and texture.

The counterintuitive truth: vague can be better than precise.

Not always. But often enough that it should make you uncomfortable.

The Inner Game

Timothy Gallwey's The Inner Game of Tennis isn't about programming. It's about performance, learning, and the relationship between conscious instruction and unconscious execution.

Gallwey makes a radical argument: sometimes the best way to improve isn't more instruction, but less. Instead of breaking down your backhand into seventeen micro-movements, you visualize the ball going where you want it. You picture the result. Then you let your body figure out the rest.

He calls this "Self 2" — the part of you that already knows how to move, that has absorbed thousands of hours of physical experience, that can execute complex actions without conscious intervention. The job of "Self 1" (the conscious, verbal mind) isn't to micromanage. It's to set the intention and get out of the way.

Sound familiar?

Prompting as Intention-Setting

I think the parallel to LLMs is striking.

The engineer's new job isn't to specify every step. It's to define the end state clearly and then trust the model to fill in the gaps. The latent space is Self 2 — a vast repository of patterns and knowledge that can be activated by the right intention.

This doesn't mean prompts should be lazy or ambiguous. Clarity about what you want matters enormously. But clarity about how to get there might be limiting.

Consider two prompts:

Over-specified:

Write a function that takes a string, splits it by spaces, iterates through each word, capitalizes the first letter of each word using substring and toUpperCase, then joins them back together with spaces.

Intention-focused:

Write a function that converts a string to title case.

The second prompt lets the model draw on everything it knows about title case — edge cases, language conventions, idiomatic implementations in whatever language you're using. The first prompt forces a specific (and probably suboptimal) implementation.

The engineer who wrote the first prompt was doing what they were trained to do: being explicit. But in the LLM context, that explicitness became a constraint.

The Uncomfortable Part

Letting go of explicit control feels wrong to engineers. We've spent careers building the muscle of precision. We've debugged nightmares caused by ambiguity. We've learned, painfully, that computers do exactly what you say — so you better say exactly what you mean.

And now the tool has changed. The LLM doesn't do exactly what you say. It interprets. It infers. It draws on context you didn't provide. Sometimes that's magic. Sometimes it's hallucination.

The new skill isn't abandoning precision — it's knowing when to apply it. Precise about the outcome. Flexible about the path. Clear about constraints. Open about implementation.

It's a different muscle. And like any new muscle, it's going to feel weird before it feels natural.

What This Means

The sandwich exercise can still be useful from a historical perspective. A lesson about how computers used to be. Worth understanding, the way it's worth understanding punch cards and assembly language. Context for where we came from.

But if you're still approaching LLMs like they're dumb terminals waiting for explicit instructions, you're leaving capability on the table. The knowledge is already there, compressed into latent space, waiting for the right prompt to activate it.

Your job isn't to teach the LLM how to make a sandwich.

Your job is to tell it you're hungry.